Merrill's Principles of Instruction are a set of instructional design (ID) guidelines that combine features of other successful ID models into one comprehensive framework. They offer a purposeful approach to course building that begins with first identifying a real-world problem and then developing practical instruction around it.

Table of Contents

- A Quick Recap of Merrill’s Principles of Instruction

- Maximizing Course Effectiveness Using Merrill’s Instructional Principles

- A Practical Example of Merrill’s Principles of Instruction

- Knowledge Check!

- Infographics

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What are Merrill’s Principles of instruction?

- What are the five stages of Merrill’s Principles of instruction?

- What is the importance of Merrill’s Principles of Instruction?

- What is an example of Merrill’s Principles of Instruction?

A general overview of Merrill’s Principles was discussed in a previous blog post. In this article, we will look at how these principles function in practice.

A Quick Recap of Merrill’s Principles of Instruction

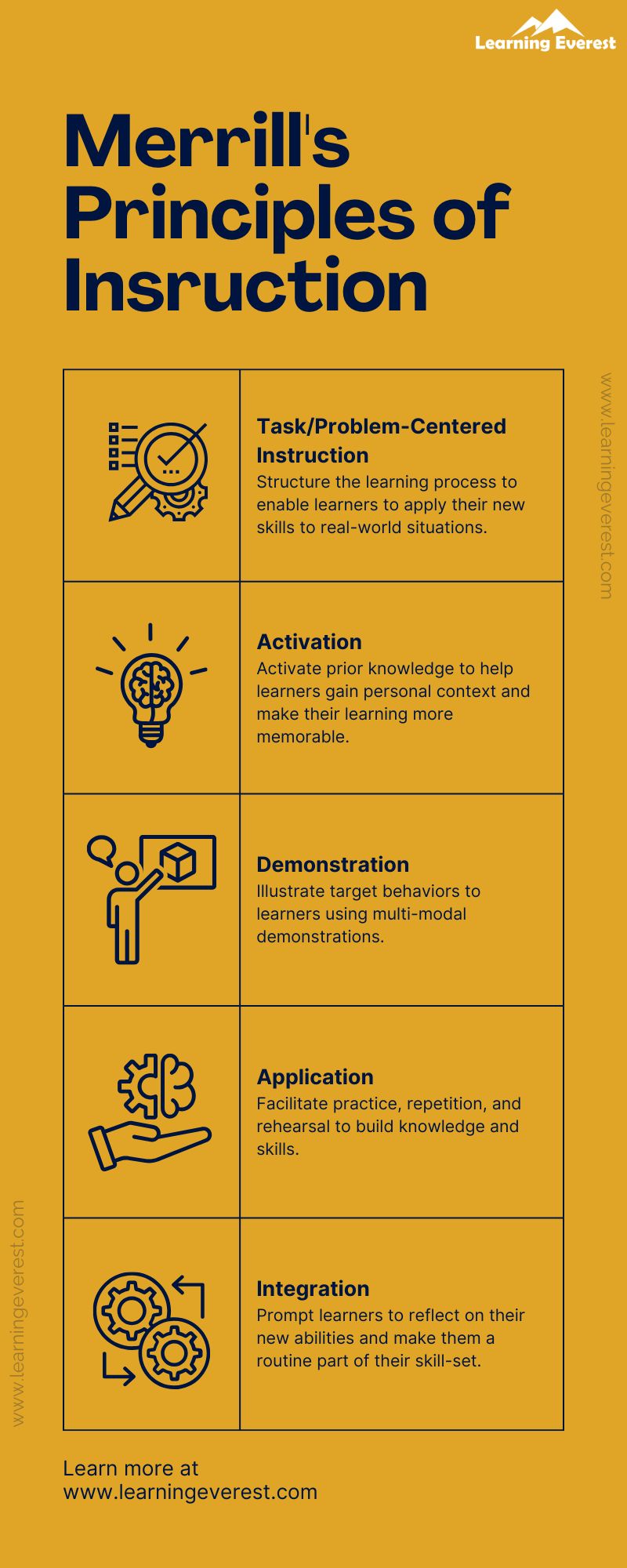

Merrill’s model prescribes five inter-related principles that are essential in the creation of enriching learning experiences. In his own words, these principles are design-oriented and view courses as products that build effective learning environments.

The first principle states that instruction should be problem or task-centered. Through the learning process, students should eventually be able to apply their new skills to real-world situations. A good course starts with simple tasks and problems and builds up the complexity. Thus, a well-defined problem or task should be at the program’s core.

The rest of the four principles form a cyclical process of instructional delivery. This cycle starts small and engages learners from the get-go. By doing so, learners receive a push to remain mindful of their existing knowledge base while learning the new information. Merrill called these principles phases. Thus, the 4 phases of effective instruction are:

- Activation: Here, learners draw upon their existing knowledge to understand the problem or task the course will be addressing. This is to get them to link new knowledge with things they already know. If necessary, fundamentals are also introduced in this phase.

- Demonstration: Using a multi-modal approach, the course facilitator illustrates the target behaviors to the learners. Depending on the course design, learners can either observe or participate in these demos.

- Application: In this phase, learners get to perform the new skills they have acquired. In the beginning, trainers provide detailed feedback to help their pupils improve. Over time, the frequency decreases to enable learners to perform these new behaviors well, even without supervision.

- Integration: The final phase is integration, where learners reflect on and discuss what they learned and add their personal touch to its application in the field.

Maximizing Course Effectiveness Using Merrill’s Instructional Principles

Merrill’s instructions are prescriptive guidelines that can be applied to any kind of course. It does not mention processes like planning learning objectives like other popular models such as ADDIE. Instead, it assumes that instructors and designers have already figured these out before jumping into instructional design.

Since the phases are cyclical and planning starts by identifying a task or problem, the sequence of steps always remains the same. Instructional designers need to plan thoroughly in advance for each step. As such, the course delivery is planned down to the T beforehand.

Gardner (2002) compiled strategies to help designers apply Merrill’s Instructional Principles based on an extensive literature review. They are as follows:

1. For Problem/Task Identification

A good direction for this principle is to pick a meaningful and authentic problem or task that students will be intrinsically motivated to tackle. Learning to solve or master these should add value to the student’s life. If the knowledge or skill cannot be broken down into smaller sub-skills or chunks, the problem might likely need restructuring.

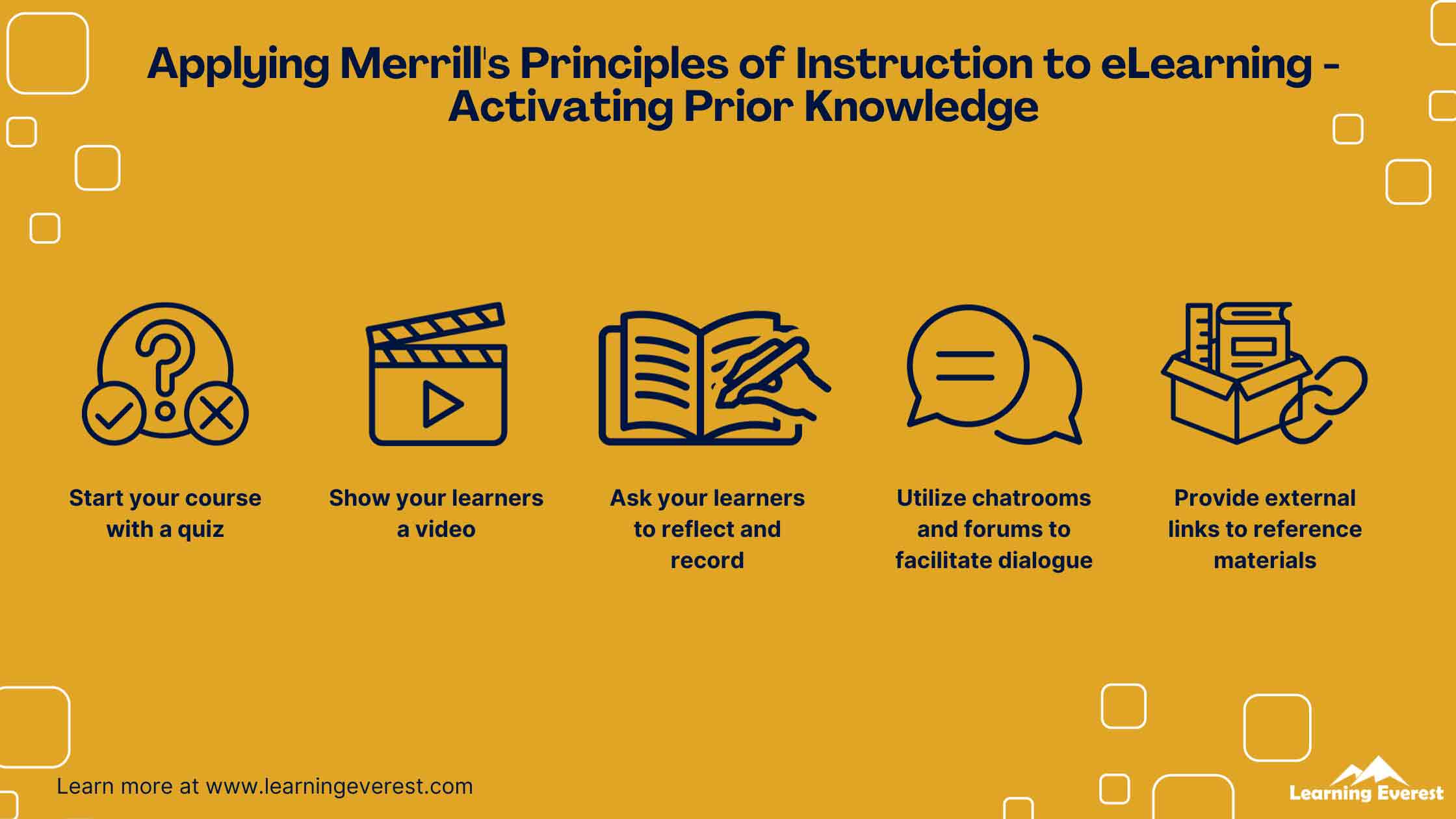

2. For Activating Prior Knowledge

There are several ways to do this. Instructional designers need to ensure that this stage caters to learners of different experience levels.

By activating prior knowledge, learners gain personal context, making their learning more memorable. Hence, this step is crucial for maximizing course effectiveness.

- Learners already familiar with the course content can be asked to share what they know as a recall exercise.

- For learners who might be new to the topic, going over the fundamentals will give them the foundation they need.

- Additionally, briefing the batch about the course structure beforehand will help them know what to expect and mentally prepare accordingly.

Applying Merrill’s Principles of Instruction to eLearning – Activating Prior Knowledge

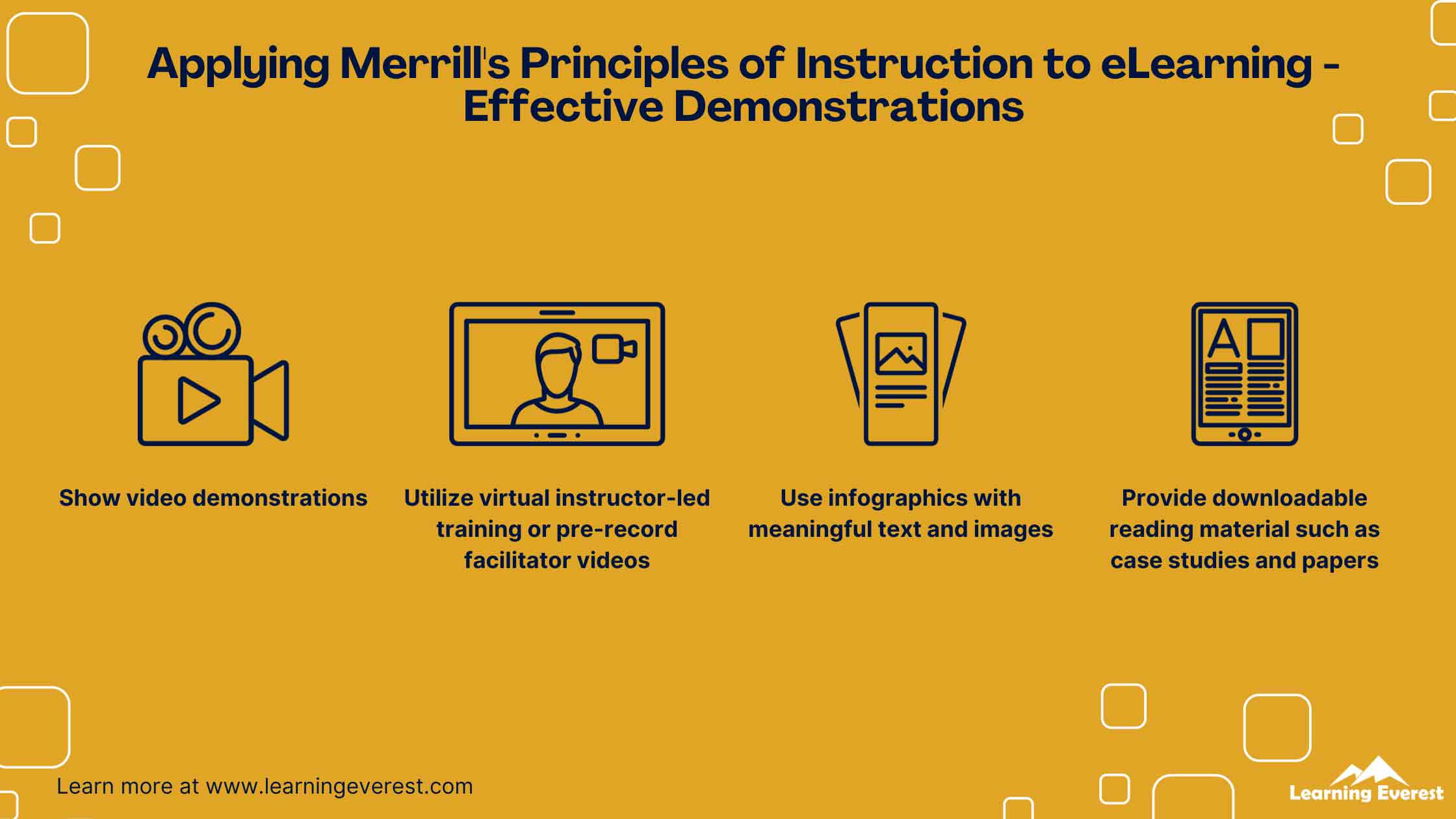

3. For Effective Demonstration

Instructors can usually get creative with demonstrations as variety enhances absorption. At the same time, they need to ensure there is a purpose and cohesion to the demos, or else the learners might get overwhelmed.

Some ways to make demonstrations multi-modal are:

- “Modelling” the behavior step-by-step. Students can grasp a lot by simply watching the instructor carry out the task. This refers to visual learning.

- Presenting new information in the context of old knowledge to make it continuous.

- Giving diverse examples and perspectives to help learners think critically.

- Frequently checking for any questions and doubts.

Applying Merrill’s Principles of Instruction to eLearning – Effective Demonstrations

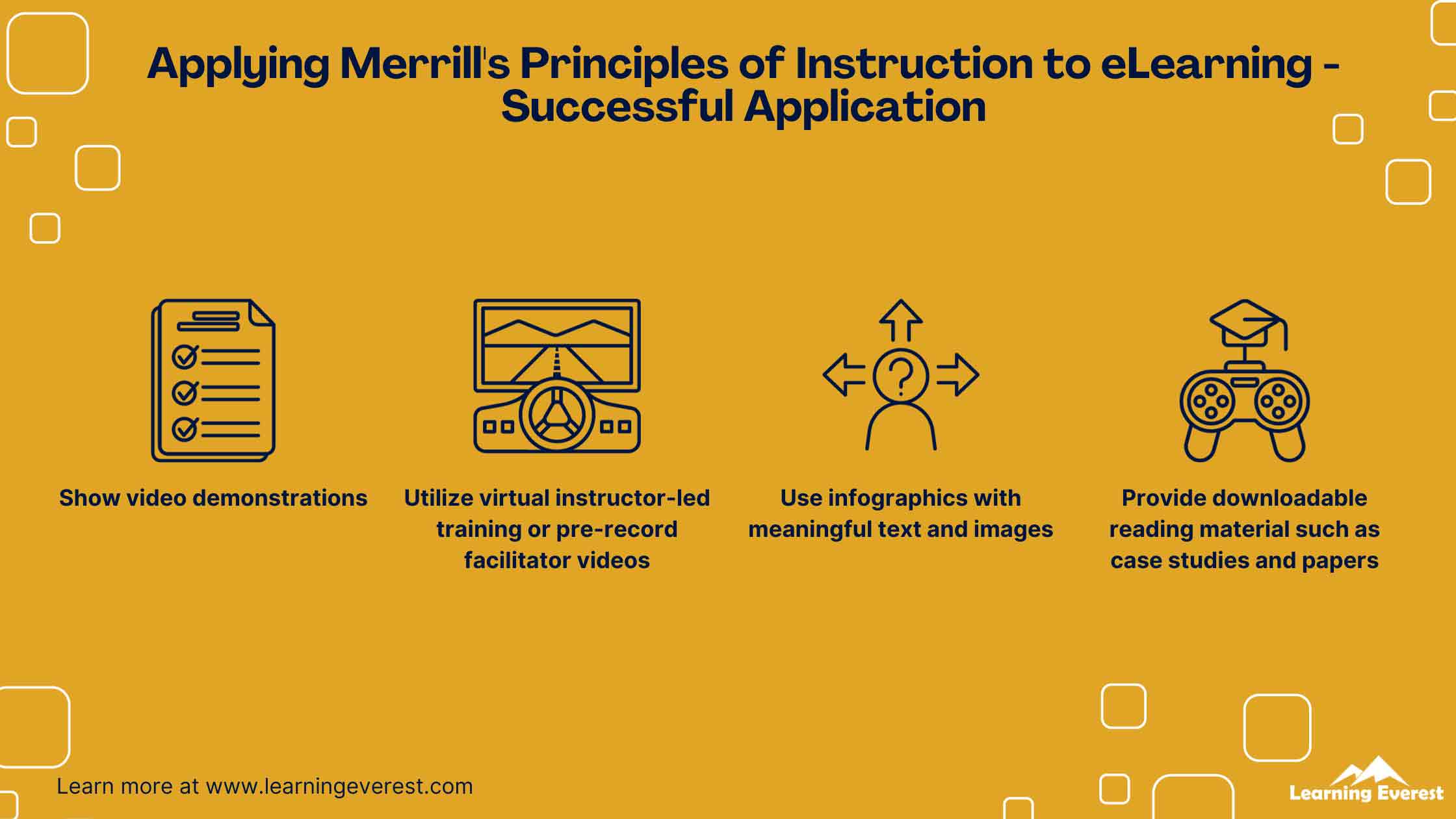

4. For Successful Application

Merrill’s Principles of Instruction place a firm emphasis on practice. Learners spend a significant amount of time building their skills and knowledge through repetition and rehearsal.

Practice starts simple and progressively gets more complex.

Additionally, introducing the subject matter in smaller steps helps build sub-skills necessary for effective real-world application.

Giving students feedback with practical demos to explain their evaluation is vital in this phase. Furthermore, there should be predetermined criteria to assess performance and guide future changes.

Verbal praise and encouragement also go a long way.

Applying Merrill’s Principles of Instruction to eLearning – Successful Application

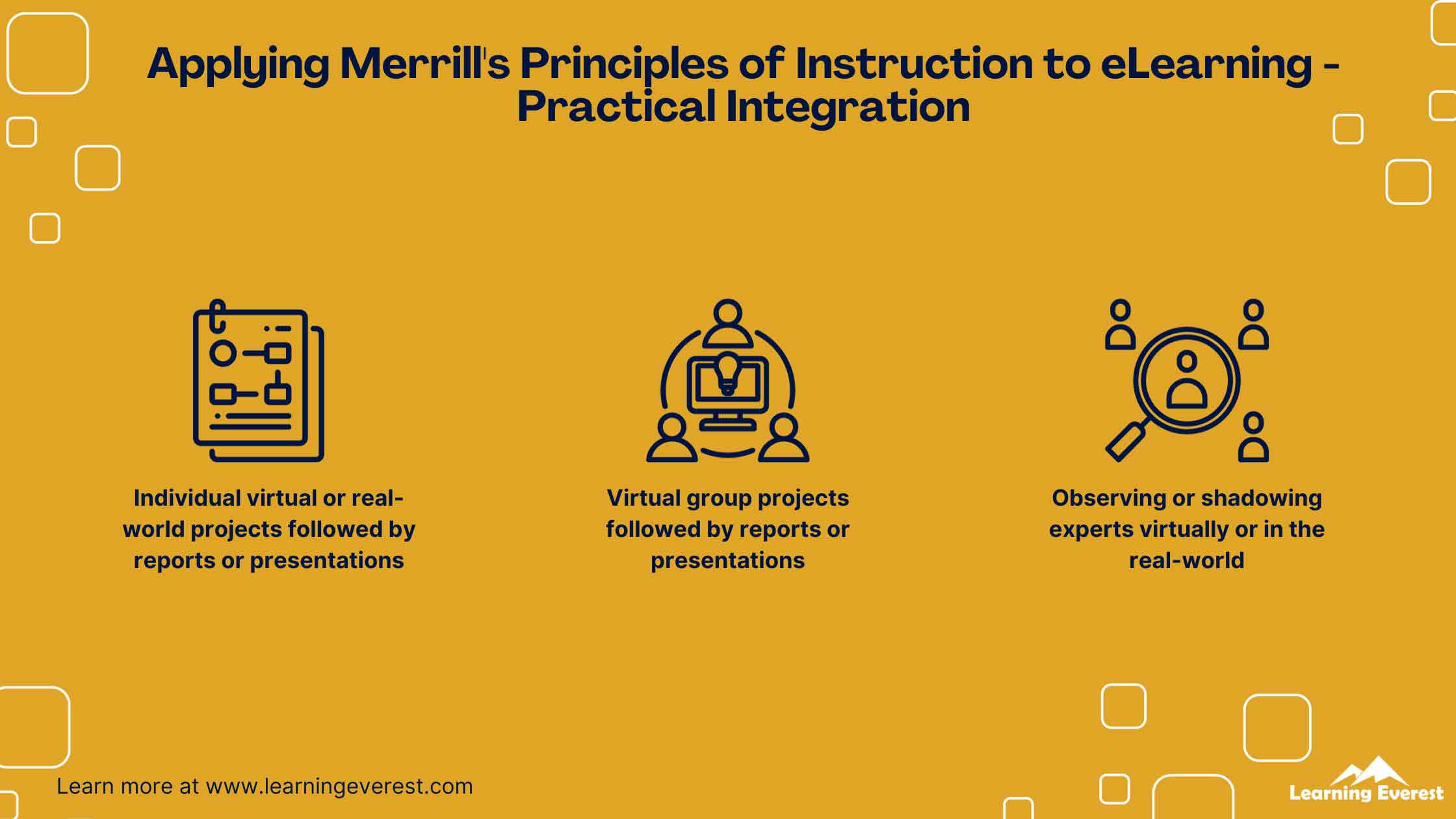

5. For Practical Integration

This is the final phase of skill and knowledge acquisition. The goal here is to prompt learners to reflect on their new abilities and make them a routine part of their skill-set.

One excellent method could be a final project with added stakes, like an internship or group project.

More often, though, instructors incorporate this principle through discussions. Learners are asked to talk about their experience during the course. They might be asked do a before and after comparison. It can also be a great technique to evoke them to reflect upon how their life will change after completing the program.

Finally, asking students for feedback and details about possible obstacles they faced will help improve the training program and help the learner contemplate potential personal barriers and oversights.

Applying Merrill’s Principles of Instruction to eLearning – Practical Integration

A Practical Example of Merrill’s Principles of Instruction

The “pebble-in-the-pond” technique is a tried and tested example of Merrill’s Principles of Instruction at play.

Merrill himself pioneered this technique. In this, the central task or problem is a “pebble” that causes “ripples” in a pool. This simply means that once the real-world problem is determined, the instructional design process expands based on it.

There are five stages or ripples in this technique. They are:

- Problem: The ripple effect begins here, i.e., the pebble. It refers to the real-world task learners will be able to accomplish at the end of the course.

- Analysis: In this stage, instructional designers and other L&D experts identify how a skill progresses from simple to complex.

- Strategy: Strategy refers to skills and knowledge learners will be instructed to build during the course.

- Design: Here, the course delivery comes together. The instructional design is developed.

- Production: In this stage, an interface is added to the course material. At this point, the course is ready to be consumed by students via a learning management or delivery system.

Like the illustration above, Merrill’s Principles of Instruction can be used to create other instructional design models. The emphasis on real-world outcomes and the methods employed to choose them are organized yet flexible due to being universal, making it simple to adapt. Thus, when building courses, instructional designers should always consider whether the content and its delivery fulfil these principles in some capacity.

Knowledge Check!

Infographics

Merrill’s Principles of Instruction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are Merrill’s Principles of instruction?

Merrill’s Principles of Instruction are a set of instructional design (ID) guidelines that combine features of other successful ID models into one comprehensive framework. They offer a purposeful approach to course building that begins with first identifying a real-world problem and then developing practical instruction around it.

What are the five stages of Merrill’s Principles of instruction?

The five stages of Merrill’s Principles of instruction are task or problem-centered subject, activation, demonstration, application, and integration

What is the importance of Merrill’s Principles of Instruction?

Merrill’s Principles of Instruction are design-oriented guidelines that treat courses as consumable products and aim to maximize student learning in a real-world context.

What is an example of Merrill’s Principles of Instruction?

The pebble-in-the-pond technique developed by Merrill himself is a model that combines all 5 principles successfully.